The SNB does not appear to pay much attention to the labour market in managing monetary policy. That may be good politics but, as I will argue below, perhaps bad economics.

For central banks it can be difficult to comment on labour markets. Very few central bankers would be willing to state in public that vacancy rates must fall, or unemployment rates must rise, for inflation to return to target. It is therefore not surprising that central banks often downplay the labour market in commenting on policy.

But there are two reasons why central banks should worry about labour markets.

Some central banks have an objective for labour market outcomes, as does the Federal Reserve. Indeed, chairman Powell discussed the labour market extensively at his recent speech at Jackson Hole. Other central banks have a secondary objective of smoothing the business cycle. That arguably involves moderating fluctuations in the labour market.

The state of the labour market may be tied to inflation, as suggested by traditional Phillips curve analysis.

Here I will demonstrate that the state of the Swiss labour market, as captured by the Beveridge curve, is strongly correlated with inflation in the period 2000-24. Although the analysis is (necessarily) simplistic, it suggests that the SNB should consider labour market conditions when judging the outlook for inflation and when setting policy.

The Swiss Beveridge curve

The state of the labour market is often captured by the Beveridge curve, that is, the relationship between vacancy and unemployment rates. The figure below shows the Swiss Beveridge curve using data from January 2000 to June 2024. The vertical axis shows the vacancy rate (the number of jobs available divided by the size of the labour force) and the horizontal axis shows the joblessness rate.

Source: SNB

There is a break in the data on vacancies in July 2018 resulting from tightened reporting requirement that led the vacancy rate to jump by 0.3%.1I therefore plot separately the curve for the period before and after this break.

Source: SNB

The figure shows an inverse relationship – the Beveridge curve – between the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate. This relationship arises through a process that matches jobseekers with vacant positions.

Consider an economic downturn. With weak activity, many workers will have lost their jobs, and few companies will have open positions to fill. With many workers looking for employment, it is easy for firms that want to hire workers to find them. Positions therefore stand vacant for short periods of time and at any point in time few positions are available.

The situation is the opposite in an economic expansion: many firms want to find new workers but there are few workers unemployed. It is therefore difficult for firms to find a good match for their vacant positions, leading to long search times and therefore to many vacant positions. As these thought experiments indicate, business cycle fluctuations will trace out the Beveridge curve.

However, and as shown by in the graph, the Beveridge curve can shift over time because of changes in the process matching workers looking for jobs with firms seeking workers.

Suppose that firms become pickier in selecting workers or that workers may be choosier in accepting job offers. With the matching process less efficient, positions will be vacant for longer periods of time. During covid workers often avoided jobs with frequent customer contact and often decided to retire early because of the risk of contagion. Since the matching process functioned less well, there were a larger number of vacant positions at any unemployment rate, that is, the Beveridge curve shifted outward.

The Beveridge curve and inflation

To see why the state of the labour market should matter to the SNB, I need a simple summary indicator of the variables in the Beveridge curve. Since neither the vacancy rate, v, nor the joblessness rate, u, can fall below zero, I will use the ratio v(t)/u(t) as my measure of the state of the labour market. That ratio will be high when the labour market is tight and low when the labour market is weak.

Below I plot it against the rate of inflation. Remarkably, both variables move strongly together during the covid period. While the correlation is high, 0.65, for the full sample, it remains substantial, 0.45, for a sample ending in 2018. The v/u ratio thus seems to capture some aspect of the inflation process.

Source: SNB

That may be for two reasons. The first is that tight labour markets lead to rising wage costs that spill over to prices. In that case I would expect the v/u ratio to be positively correlated with nominal and real wage growth.

The second is that the v/u ratio simply captures the strength of aggregate demand in the economy. In that case I would expect the correlation with nominal wage growth to be low and the correlation with real wage growth to be negative.

Unfortunately, there are only annual data on wages in Switzerland staring in 2010. But looking at the correlation between v/u ratio and wage growth over the short period 2011-23, I find that the correlation with nominal wage growth is 0.38 and with real wage growth -0.79. This suggests that v/u is best thought of as capturing the level of aggregate demand in the economy.

What does the v/u ratio signal now?

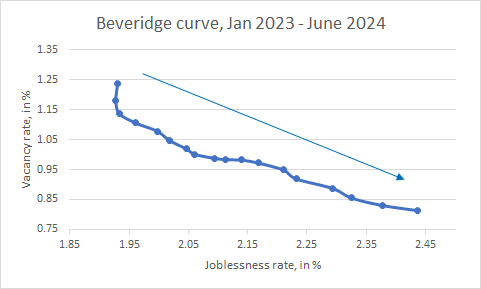

With that in mind, it is instructive to look at the Beveridge curve since early 2023. The graph below shows that the joblessness rate has risen by about 0.5% and the vacancy rate has fallen by around 0.35% in this period.

Source: SNB

This segment of the Beveridge curve shows a continuous slowdown in the Swiss labour market in the last 18 months of data. Following the analysis above, that suggests falling inflation pressures.

Conclusion

The tightness of the Swiss labour market appears strongly correlated with inflation pressures. With the labour market weakening and inflation therefore abating, the SNB has room to cut interest rates in September.

The work reported here is preliminary and may be subject to errors. It should not be seen as constituting investment advice. Readers are advised to seek professional investment advice.

Employers became obliged to report job vacancies in some professions with over 8% unemployment. See https://www.altenburger.ch/blog/job-vacancy-reporting-duty-for-swiss-employers

What do you reckon are the predominant shocks hitting the Beveridge curve in Switzerland over the period for which you have wage data @Stefan? I’m just thinking that you could have a structural break in the relationship with inflation if Covid was a major reallocation shock rather than an aggregate demand shock.