In an earlier post I looked at the Swiss Beveridge curve – which is traced out by the ratio of the vacancy rate to the joblessness (or unemployment) rate – and showed that it has been strongly correlated with inflation since 2000. I concluded that the SNB should consider the state of the labour market when setting monetary policy.

In this post I look more closely at the Swiss labour market as a driver of inflation. One conclusion is that while both the vacancy and unemployment rates matter for inflation, the vacancy rate leads the unemployment rate and is thus a timelier measure of labour market tightness.

Another is that the state of the labour market points to further declines in inflation. The SNB should therefore cut rates in December. From today’s vantage point I think cutting by 0.5% makes sense but there is still more than a month before the next policy meeting.

The Swiss labour market

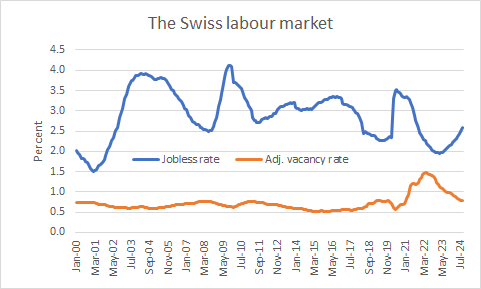

Analysing how the Swiss labour market impacts on inflation is made difficult by the lack of high frequency data on wages. However, there are monthly data on vacancy and joblessness rates that can be used since they matter for inflation. The figure below shows these data series from January 2000 to September 2024. For the reasons explained in my earlier post, I use the “adjusted” vacancy rate (defined by the actual vacancy rate + 0.3% before July 2018).

Source: SNB

The graph shows that the two series move with the business cycle. Thus, the start of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and the covid pandemic are both apparent. The joblessness rate has risen sharply, and the vacancy rate fallen, over the last over two years, indicating how the labour market has weakened.

As one would expect, the two series are inversely related. Interestingly, the highest correlation is between the current joblessness rate and the vacancy rate six months earlier (that correlation is -0.54; the contemporaneous correlation is -0.47). That suggests that the vacancy rate is an early indicator of the tightness of labour markets.

Phillips curves

Next, I estimate some simple Phillips curves. As a preliminary, I looked at the pattern of Granger causality, which indicated that the labour market variables contained information useful for forecasting future inflation, but that the converse was not true. It thus seems that the labour market is a driver of inflation.

I went on to estimate Phillips curves on the annual inflation rate, since the data were not seasonally adjusted. I allowed a lagged inflation rate. Preliminary regressions indicated that the change in the labour market variables should be used as regressors.

The estimates below show that the labour market variables are all drivers of inflation. Indeed, the results appear not to be very sensitive to the exact variable used. Interestingly, the lagged change in the vacancy rate is marginally more significant than the contemporaneous variable, pointing to the leading indicator property of vacancies.

Source: my estimates as described in the text. t-statistics in parentheses

Implications for SNB policy

The implications for SNB policy seem clear. The state of the labour market is an important driver of inflation in Switzerland. While it is still marginally tighter than on average over the last quarter century, it has weakened markedly since the SNB — and other central banks — started to tighten monetary policy in 2022 to deal with surging inflation. The risk that it will continue to worsen seems clear. I think that the SNB should cut by 0.5% in December to prevent inflation from falling to zero. Indeed, by taking prompt action now, rather than waiting and running the risk that inflation will fall further, the SNB can reduce the likelihood that it will have to return to zero or negative interest rates.