In my last post, I argued that monetary policy should not be viewed purely as a domestic response to national economic conditions. Instead, central banks around the world often change interest rates at roughly the same time and in the same direction because they face broadly similar—though not identical—economic conditions.

In this post, I expand on that idea by looking at interest rate decisions across a set of advanced-economy central banks.

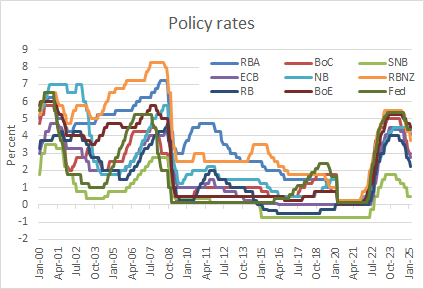

Using monthly policy rate data from the Bank for International Settlements, I examine the path of interest rates set by nine central banks since 2000: the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada, the Swiss National Bank, Norges Bank, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Riksbank, and the Bank of England.

Source: BIS

It is readily apparent that the interest rates set by these central banks have moved closely together since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020. But this is not a new phenomenon. There were earlier episodes of tight co-movement as well—most notably in the lead-up to the global financial crisis that began in 2008, when most of these central banks were raising rates in tandem. And they all cut rates as the financial crisis took hold.

A second graph helps put these comovements in context. It shows the median policy rate across these central banks, along with the interquartile range. These are robust measures of central tendency and dispersion that are less sensitive to outliers than the mean and standard deviation.

Source: my calculations on BIS data

Two points stand out:

While the median interest rate never fell below zero over this period, the lower edge of the interquartile range was at 0% from January 2020 to April 2022, as central banks cut interest rates to their effective lower bounds during the pandemic.

The interquartile range is asymmetric: when central banks are tightening policy, the upper quartile tends to rise more sharply than the median. In easing cycles, the interquartile range is compressed.

These strong comovements reflect the fact that economic conditions are correlated across countries. This raises an important question: can we use interest rate decisions by other central banks to predict the next move by the domestic central bank?

The rationale behind focusing on foreign central bank decisions is twofold.

Economic data are noisy. Key indicators like inflation or GDP are published with a lag, frequently revised, and often distorted by one-off events. Temporary shocks—such as labour strikes, weather disruptions, or even hosting the Olympics—can obscure underlying trends. And different data series are often contradictory. This makes it difficult not just to interpret the data, but to anticipate in real time how central banks will respond to them.

Interest rate decisions by central banks are available immediately and reflect a careful assessment of local economic conditions. Each decision is a judgment call made after sifting through exactly the kind of inconsistent, volatile data described above. In this sense, policy rates act as summary statistics of economic conditions. And since those conditions are correlated across countries, the interest rate decisions of foreign central banks should contain useful information about domestic economic conditions—and, by extension, about the likely path of domestic interest rates.

To illustrate this argument, I computed—for each central bank—the median policy rate of the other eight central banks. I then examined whether changes in this median helps predict future changes in the domestic interest rate.1

Source: My calculation on BIS data.

The findings are striking. In seven out of nine cases, the median interest rate set by the other eight central banks provides statistically significant information about future domestic policy rate changes (in the sense that changes in the foreign median Granger-causes changes in the domestic rate). The only exceptions are the Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

For the rest—including the ECB, SNB, BoE, and others—changes in the median interest rate set by foreign central banks last month is informative about what the domestic central bank is likely to decide this month.

Conclusion

Interest rates set by the domestic central bank are partially shaped by global economic conditions. Central banks’ policy decisions are therefore more correlated than is often assumed. That opens new ways to think about forecasting monetary policy: if you want to know what your central bank will do next, watch what other central banks are already doing.

The views expressed are my own. The work presented is preliminary and may contain errors. It should not be construed as investment advice. Readers are encouraged to seek professional investment guidance.

To be clear, I computed Granger causality tests on the changes in the domestic policy rate and in the median interest rate, using two lags.

Thanks, Stefan. This is a great post! Your analysis reminds me of the insight of H. Rey's "Dilemma not Trilemma: the Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence," in which she argues that it is hard to maintain monetary policy independence under financial integration. The set of countries you are focusing on are indeed quite financially integrated, and one aspect of further investigation might be to see if this conjecture would hold if there is sufficient time series variation in the proxy measure of financial integration within the period you are focusing on.