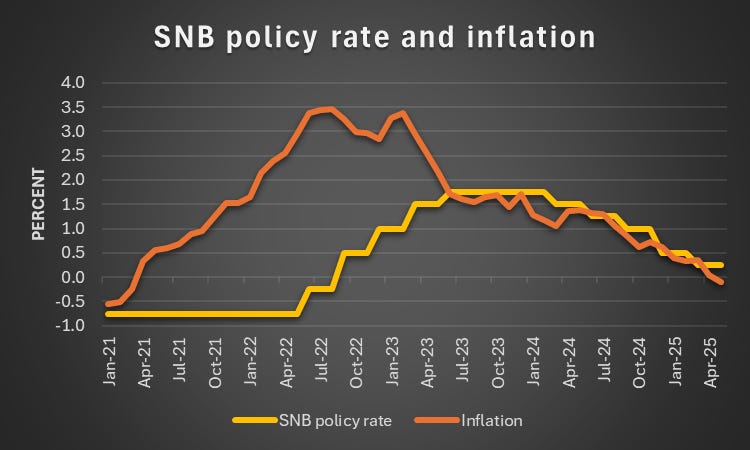

Punchline: Swiss inflation has turned negative. After hitting 0.0% in April, it fell to ‑0.10% in May. A combination of global disinflationary forces and the turmoil triggered by the recent US trade policy announcements has strengthened the franc and led energy prices to fall. What should the SNB do? In my view, a return to negative interest rates would be premature and disproportionate. Inflation is low, but the case for urgent action is weak.

A Disinflation Shock

Inflation in Switzerland has returned to very low levels. After falling to 0.0% in April, it declined to ‑0.10% in May, that is, below the SNB’s 0-2% definition of price stability.

This drop reflects two powerful forces. First, a long stretch of global disinflation has left price pressures subdued across advanced economies. Second, the Trump Administration’s trade policy announcements on “Liberation Day” on 2 April that triggered financial market turmoil, a depreciation of the US dollar, and falling energy prices as investors began to anticipate a global slowdown. The combined effect has been deeply disinflationary for Switzerland.

Source: SNB and BfS

The question now is: how should the SNB respond?

Two views are emerging. The mainstream view—one I share—is that the SNB should cut interest rates by 25 basis points to 0.0% at its meeting next week. A more aggressive alternative is gaining traction: that the SNB should cut by 50 basis points to ‑0.25%. This view rests on the argument that negative interest rates are warranted and that delaying the adjustment serves no purpose.

A Changed Governing Board

Relatedly, some observers have suggested that the SNB’s reaction function has become less predictable, pointing to the policy decisions in September and December last year. This raises the question of whether the change in the Governing Board last autumn may be a factor.

Monetary policy at the SNB is complicated by its unusually small Governing Board. In large policy committees—such as the ECB’s 26-member Governing Council—individual members have little weight. Since policy is set by the median member, it is common for individuals to find themselves in the minority.

Many years ago, when I was at the BIS, a member of the SNB’s Governing Board explained to me that the three-person structure imposes particular constraints. In a group that small, being in the minority means being alone. And because the same three individuals are also responsible for managing the institution, persistent disagreements about policy can spill over into broader internal tensions.

In his view, it would be especially difficult if the Chairman were in the minority, given his role as the bank’s public face. Consensus is therefore essential in a committee that small. The structure, he concluded, requires a Chairman who can build and sustain that consensus.

Following the retirement of Thomas Jordan last year, the Governing Board lost its most experienced member and a highly respected macroeconomist. Jordan’s long tenure and authority commanded respect both within the Board and among the broader public. It is easy to imagine that the tone and dynamics of Board meetings have shifted over the past year—and that policy clarity may have diminished as a result.

Why a Modest Cut Makes Sense

It is against this backdrop that the SNB must now decide whether to cut interest rates—and by how much.

The case for a 25 basis point cut rests on a conventional reading of the data. Inflation has fallen sharply, the franc remains strong, and global disinflationary pressures continue to build. A modest easing would signal that the SNB remains committed to its price stability objective, while avoiding the more disruptive effects of negative interest rates.

The alternative view calls for a bolder move: a 50 basis point cut. Financial markets currently attach about a 30% probability to that outcome. Advocates argue that inflation is below target and that delaying the adjustment risks allowing inflation expectations to drift lower. If a return to negative rates is ultimately needed, why not act decisively now?

Of course, the argument that the SNB should simply bite the bullet and reintroduce negative interest rates to “get the job done” has a certain appeal. It suggests decisiveness and a willingness to act forcefully when needed. But this line of reasoning misses the key issue the SNB faces now: negative interest rates are not just another step in easing—they are a qualitatively different tool, with added complications. Is going below zero—and accepting the complications that come with it—justified in the current context?

Negative Rates: A Tool Best Used Sparingly

In my view, negative interest rates remain a useful policy tool, but one that comes with complications and political sensitivities. These made the earlier period of negative rates particularly contentious. For that reason, they should be used sparingly. Reintroducing them hastily—when they may not be necessary—is unlikely to be a winning strategy.

I remain unconvinced that negative interest rates are needed now.

First, the outlook for US trade policy remains highly uncertain. Although the Trump Administration has announced sweeping tariffs, it has already delayed the imposition of some and granted exemptions for others—seemingly in response to the sharp market reaction. Some commentators argue that the tariffs are primarily a negotiating tactic, intended to strengthen the US position, and will ultimately be scaled back once new trade agreements have been reached. And a tariff-induced recession would pose a major political risk for the Republican Party ahead of the 2028 election. In short, it is far too early to conclude that the tariffs as announced will be fully implemented or permanent. Indeed, they likely will not be.

Second, the situation the SNB faced when it introduced negative interest rates in December 2014 was very different from today. At that time, the SNB operated with a minimum exchange rate of CHF 1.20 per euro and was under strong pressure to prevent franc appreciation. When the minimum exchange rate was lifted in January 2015, markets expected a sharp and immediate rise in the franc’s value—the only question was how far and how fast. While the franc has strengthened recently, a surge seems unlikely today.

Third, there is no evidence that the Swiss economy is slowing precipitously—or at all. The low inflation largely reflects imported goods becoming cheaper. Services and domestic inflation stood at 1.05% and 0.62% in May. These are not levels that justify immediate mitigating action.

The Medium Term Matters

I agree with SNB Chairman Martin Schlegel, who recently said that the SNB does not have to react to one or a few months of negative inflation but should focus on the medium term. That view is consistent with the logic behind average inflation targeting.

However, while an emphasis on the medium term makes good sense, it is nowhere to be seen in the SNB’s formal definition of price stability, which states: “the SNB equates price stability with a rise in the Swiss consumer price index of less than 2% per annum.” To better reflect the SNB’s actual policy approach, the phrase “in the medium term” should be added to that sentence.

When Might Negative Rates Be Justified?

Taken together, these points suggest that a return to negative interest rates would be a premature and disproportionate response. The case for urgent action is weak: the outlook for trade barriers remains uncertain, there is no reason to expect a further surge of the exchange rate, and domestic inflation dynamics do not indicate a collapse in underlying demand. In this context, a measured 25 basis point cut to 0.0% would be sufficient. It would acknowledge the recent decline in inflation without overreacting to developments that may yet prove temporary.

Under what conditions might the SNB adopt negative interest rates? I interpret the SNB’s position as saying that while it will not hesitate to introduce negative interest rates if necessary, it much prefers not having to do so. Thus, the bar for reintroducing negative rates is high. Nevertheless, it could happen under two circumstances:

Sustained inflation far below zero. However, a one-off appreciation of the exchange rate or a drop in energy prices will depress inflation only temporarily and are consequently not enough to trigger an extended period of falling prices.

A domestic recession. A sharp economic slowdown that pushes down markups and wage growth for an extended period—leading to weak growth and rising unemployment—would warrant stronger policy support.

That is what we must watch for in the data.

Thanks, Stefan, for the very clear and well-structured summary of the current policy debate. It would be interesting to see the conditional inflation path assuming a likely 25bps cut, and to understand how much tolerance the SNB has for a few negative CPI inflation prints. Looking ahead, global risks could put further upward pressure on the Swiss franc, while additional disinflation may come from the rental component of the CPI basket.