The Fed Holds Steady

What Comes Next for US Monetary Policy?

With the FOMC having left interest rates unchanged at its meeting on May 6–7, this is a good time to review the outlook for US monetary policy.

In an earlier post, I noted—along with many other commentators—that the recently announced increases in US tariffs would raise inflation and slow the economy and thus be stagflationary. While the size of these effects and their relative magnitudes are unclear, a Taylor rule analysis suggested that, for plausible assumptions, the Fed should not change interest rates in the short run. I also noted that a sharp reduction in rates would only be appropriate if the economy were plainly sliding into recession.

In a related post, I suggested that, in the current situation, central banks should be patient, focus on hard data rather than soft survey data, and remain guided by their mandates. There is a risk that the Fed—and other central banks as well—could overreact to the shift in US trade policy.

While the tariff announcements have weighed heavily on sentiment indicators, these are often volatile and reflect anticipated rather than actual economic developments.

There are good reasons to doubt that US tariffs will be raised as much as initially announced. The administration has in several cases adjusted its position, introducing exemptions or delaying implementation. Some tariff announcements may also be intended principally to strengthen the US position in trade negotiations. In many cases, actual tariffs may end up being lower than initially indicated—or may not be imposed at all.

It therefore makes sense for the FOMC to downplay the downside risks to growth and the upside risks to inflation implied by sentiment indicators and instead wait for hard economic data to indicate whether conditions are indeed deteriorating. While the risks are apparent, it is not certain that they will materialise. The FOMC should therefore be patient and reconsider policy meeting-by-meeting.

The US Economy

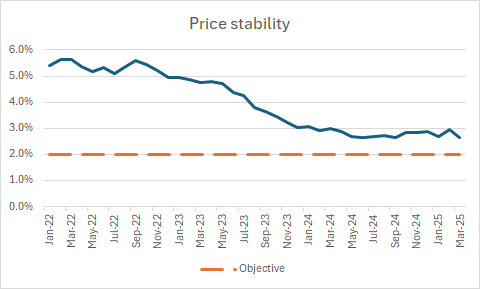

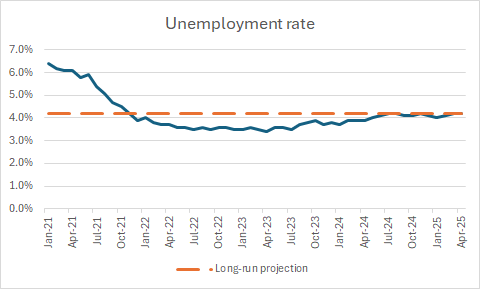

Given its dual mandate of price stability and full employment, the Fed will pay close attention to movements in core PCE inflation and the unemployment rate. Neither indicator currently shows signs of deterioration.

Core PCE inflation—the FOMC’s preferred measure of price increases—declined in 2022–24 and fell to 2.6% in June 2024 but has not decreased further since then. The fact that core inflation has not moved closer to the 2% target must be a concern for the FOMC. It provides a good reason not to cut interest rates.

Source: FRED

Similarly, the unemployment rate remains at 4.2%, which corresponds to the median long-run projection of FOMC members which we can think of as an unemployment “target.” Overall, it is difficult to see the FOMC cutting interest rates in the current economic environment of inflation above target and unemployment at target.

Data: FRED

The FOMC Meeting

At last week’s meeting, the FOMC maintained its “wait-and-see” approach. The committee acknowledged that uncertainty has increased and that there are risks of both higher inflation and weaker activity.

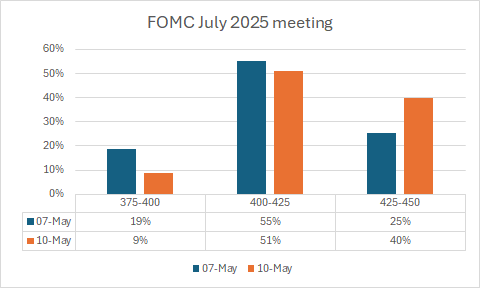

Furthermore, the Committee appeared unlikely to adjust policy without clear evidence of labour market deterioration. In response, market participants have lowered their expectations of rate cuts during the remainder of the year. That said, a renewed rise in inflation pressures arising from the imposition of tariffs that forces the Fed to change the direction of policy cannot be ruled out.

While expectations still point to a first cut in July, the odds have become more balanced. For instance, comparing CME data on market expectations on the mornings of May 7 and May 10, the likelihood of no change in interest rates in July rose from 25% to 40%.

Source: CME

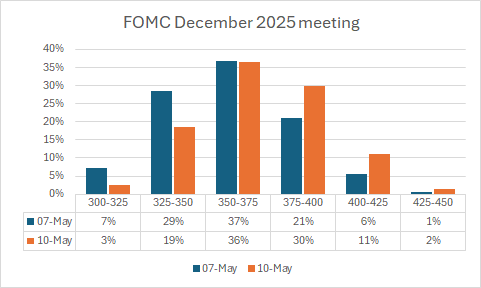

Similarly, while markets still expect three cuts by the December meeting, the probability of two or fewer cuts increased from 28% before the meeting to 43% afterward.

Source: CME

Of course, the FOMC’s future policy decisions will depend on how the data evolve in the coming months. Market expectations are likely to remain highly sensitive to new macroeconomic information, and it may take relatively little for these probabilities to shift further.

The outlook

Overall, the outlook for interest rates remains highly uncertain. It is possible that matters will become clearer by the time of the June meeting. For now, no change in interest rates is expected before the July FOMC meeting, which will take place on July 29–30. The key releases ahead of that meeting include PCE inflation on May 30 and June 27, and unemployment on June 6 and July 3.

Really interesting read on the Fed's approach. Made me think how we're all getting carried away with the tariff drama instead of just looking at the actual numbers.

The tariff situation with China is mad. Trump announces these ridiculous levels, then "slashes" them by 115% down to 30%, and somehow the market treats this as good news! It is a classic negotiation tactic - start with something outrageous so your real target seems reasonable. If he'd gone straight to 30%, markets would've had a meltdown. But now everyone's breathing a sigh of relief over what's still a bloody enormous tariff!

Those dates for the upcoming data drops are worth sticking in your calendar. The PCE stuff end of May and June, plus those job numbers, will tell us far more than all this endless chatter.

That chart of shifting market expectations after the FOMC meeting really nails it - we're finally waking up to the fact that rate cuts aren't the sure thing we thought. With inflation still above where they want it and unemployment exactly where they're aiming for, the Fed's got no reason to rush. Can't really blame them for sitting tight while everyone else runs around like headless chickens!