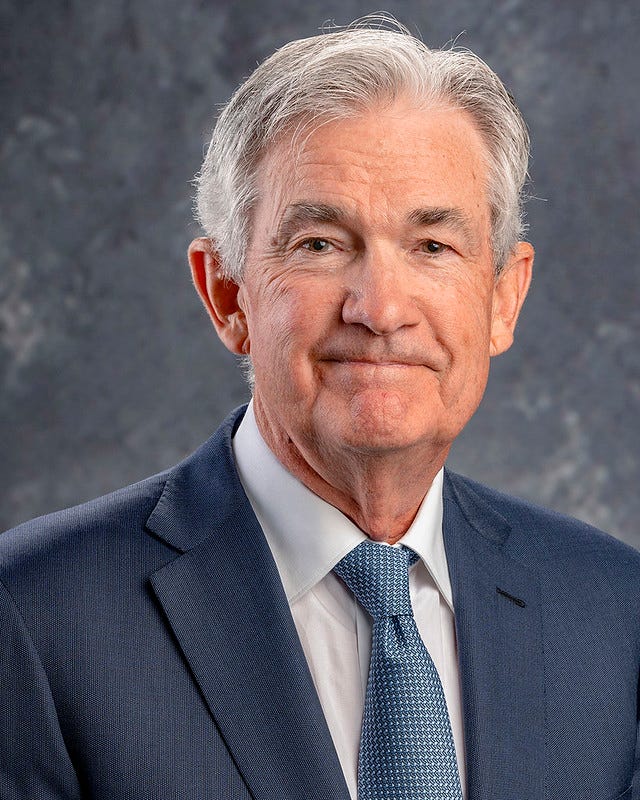

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Chairman Powell’s recent speech at the Jackson Hole Symposium has attracted much attention. The speech has been interpreted as signalling that the Fed will (most likely) cut interest rates in September. But it also contained important information about how the Fed will set policy in the coming months that should not be overlooked.

Many commentators have quoted Powell as saying:

The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

They conclude that the Fed will cut interest rates in September and speculate whether they will do so by 0.25% or 0.50%. While individual FOMC members may have a view, that question is premature since much of the data the Fed focus on has not yet been published. It could be unexpectedly weak or strong, and the Fed will react accordingly.

My take on the speech is a little different. Words have meaning. Central bank speeches are written with great care and should be read in the same way. While the speech undoubtedly signals that rate cuts will be coming, what it says about how the Fed will react to incoming data is more important. Market participants should focus on this.

Powell starts by explaining that in recent years, the FOMC has focused single-mindedly on bringing down inflation because it was so high. And since the labour market was tight, there was no conflict between the Fed’s two objectives:

For much of the past three years, inflation ran well above our 2 percent goal, and labor market conditions were extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) primary focus has been on bringing down inflation.

He goes on to say that because inflation has declined substantially and labour markets have normalised, the situation is now different:

… the balance of the risks to our two mandates has changed.

Inflation is now much closer to our objective …

… the labor market has cooled considerably from its formerly overheated state.

Risks have now become symmetric and the trade-off between inflation and full employment has been restored:

The upside risks to inflation have diminished. And the downside risks to employment have increased. As we highlighted in our last FOMC statement, we are attentive to the risks to both sides of our dual mandate.

That leads to what I regard as the most significant passages in the speech, in which Powell makes clear that the Fed is particularly worried about the labour market and will prevent it from weakening further:

We do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions.

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market …

The current level of our policy rate gives us ample room to respond to any risks we may face, including the risk of unwelcome further weakening in labor market conditions.

So, on my reading, Powell is signalling that the Fed is once again balancing risks to inflation and labour markets. And it is much more sensitive to labour market weakness than to inflation a little above target.

If so, market participants should focus squarely on the incoming labour market statistics and not be overly concerned if inflation takes some time to fall to 2%. That makes good sense – central banks should respond to the determinants of inflation, not just inflation. Indeed, if monetary policy was perfect, inflation would always be at target and the central bank would move interest rates around vigorously in response to economic developments that risk pushing inflation away from target.

But I could be wrong. We shall see.