Could the US Default on its Public Debt? Lessons from 1933

Source: Federal Reserve Board. President Roosevelt signs the Gold Bill, January 1934.

Punchline: While a US default on its public debt may seem implausible, history shows it is not impossible. In 1933, the Roosevelt administration effectively defaulted by abolishing gold clauses on bonds and devaluing the dollar, reducing the value of repayments to creditors. While that episode was necessary to revive the economy, but it still altered agreed repayment terms. Today, such a move would be seen as bad faith and poor economic management, yet the precedent reminds investors that what has happened once can happen again.

The United States is running large budget deficits. In the spring, before the “Big Beautiful Bill” became law, the Congressional Budget Office projected that federal debt would rise from around 120% of GDP in 2025 to more than 150% by 2055. Forecasts are uncertain, but the debt is very large, growing rapidly, and must eventually be brought under control. The question is how.

Most commentators see the idea of a US default as so remote that it is not worth considering. There are no signs that domestic or foreign investors fear the US will have difficulty meeting its obligations. The Treasury market is deep and liquid, and the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency. Yet the United States has, in effect, defaulted before. It was not called that at the time, but the impact on creditors was the same: they were repaid on less favourable terms than originally agreed. The precedent — the abrogation of gold clauses in 1933 — offers a lesson worth recalling.

Before reviewing that episode, three points deserve to be made. First, markets rarely anticipate defaults. They tend to happen, as Ernest Hemingway wrote of bankruptcy, “gradually and then suddenly.” For investors in US public debt, it is prudent to think about what appears unthinkable — not because it is likely, but because it is possible.

Second, if a US default were to occur, it would almost certainly be partial and disguised under another name — perhaps framed as a fair adjustment or a necessary step to correct an imbalance.

Third, a precedent for such thinking already exists in US trade policy. Tariffs have been justified as a way to make trading partners “pay their fair share” and to offset perceived disadvantages.

In 2023, Stephen Miran — now chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and a nominee for the Federal Reserve Board — applied similar reasoning to debt markets. He suggested a “user fee” on foreign official holders of Treasury securities to weaken the dollar and compensate the US for the security it provides to other countries. If such a measure applied to existing bonds, it would reduce payments to creditors in much the same way as a partial default.

A Precedent from the 1930s

With that as background, we turn to the events of 1933, when the US was in the grip of the Great Depression. A central problem then was the fall in prices from 1929 onward, which increased the real burden of debts. Firms, banks, and households that had borrowed expecting prices and wages to keep rising instead saw them decline. Debts became heavier in real terms, forcing sharp cutbacks in spending, triggering defaults, and contributing to mass unemployment.

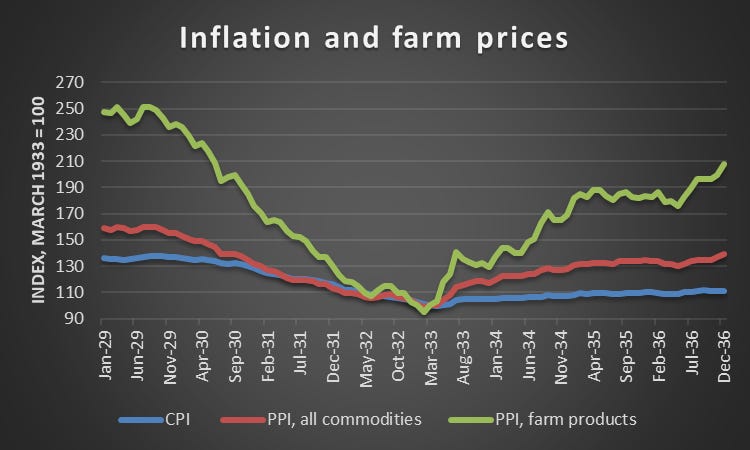

President Franklin Roosevelt recognised that ending the downward spiral required raising prices. He was particularly concerned about the need to raise agricultural prices. The graph below shows how the CPI and the PPIs for commodities and farm products all declined until 1933.

Source: FRED

But with the US on a gold standard — de facto since the 1830s and de jure since 1900 — that meant the dollar had to be devalued, which in turn required breaking its link to gold.

Many US public and private bonds carried a gold clause, guaranteeing repayment in gold or its equivalent. If the dollar were devalued while these clauses remained, the government and other borrowers would face a higher dollar cost of servicing their debts, undermining the purpose of devaluation. To avoid this, Roosevelt in 1933 abolished the gold clauses and then devalued the dollar. Creditors lost the right to be repaid in gold, receiving instead dollars worth less in gold terms.

The gold policy unfolded in stages. In early 1933, gold was flowing out of the Federal Reserve as domestic holders preferred coins to deposits or paper currency, and foreign investors feared devaluation. By March, the New York Fed could no longer convert currency into gold. Roosevelt declared a national banking holiday. Congress gave him control over gold movements and empowered the Treasury to compel the surrender of gold coins and certificates.

Outflows continued, and in April the gold standard was suspended. Gold exports and domestic conversion were banned, halting the drain. In May, the Thomas Amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act authorised the president to reduce the gold content of the dollar by up to 50% and to back it with silver or a mix of metals.

In June, Congress voided gold clauses in all contracts, public and private, removing the legal guarantee of repayment in gold or its equivalent. The Supreme Court upheld the measure in 1935 in a series of 5–4 decisions.

In January 1934, the dollar was formally devalued by President Roosevelt signing the Gold Bill. Gold was priced at $35 an ounce, compared with $20.67 since 1900. This cut the gold value of the dollar by 41%. Ownership of all monetary gold passed to the Treasury, and creditors were paid in depreciated dollars.

The effect of the abolition of the gold clause was identical to a partial default, though it was presented as a necessary step to revive the economy. By increasing the price level, devaluation reduced real debt burdens, encouraged spending, and supported recovery.

Borrowers in the 1930s may not have been severely harmed. Roosevelt’s policies restored improved the creditworthiness of many debtors, allowing some lenders to recover payments that might otherwise have been lost. In that sense, while creditors were not paid in gold, there was a case to be made that the policy served their longer-term interests as well.

Parallels and Lesson

The parallels with the present situation are clear. A default today would also involve changing repayment terms in a way that reduces value to the creditor. One possibility is that Stephen Miran’s proposal for a “user fee” on foreign holders of US Treasuries could eventually be put into practice. It would be justified as necessary for the broader good. It would disproportionately affect foreign investors, who have less political influence. And it would be framed as a policy adjustment, not as a default.

The lesson is equally clear: defaults can happen in the United States, even if they are not called that. But the situation today would be very different from the 1930s. The Great Depression was an extraordinarily deep downturn with massive economic and social costs, often viewed less as the result of policy mistakes than as an unavoidable calamity — an economic act of God. A partial default now would be widely seen as an act of bad faith and a sign of poor economic management, and markets would be likely to react far more negatively than they did ninety years ago. Holders of US Treasury debt should be mindful that what has happened once can happen again.