Comments on Beyond the Taylor Rule

Credibility, expectations, and why central banks bent the rules

Source: John Taylor

Punchline: In a widely quoted paper presented at Jackson Hole, Emi Nakamura and her coauthors examine why central banks did not follow the Taylor rule when inflation rose sharply in 2021–22. They argue that policymakers held back because many believed the shocks were temporary, supply and demand effects were correlated, and credible central banks could afford to wait.

Few ideas in monetary economics have been as influential as the Taylor rule. John Taylor’s 1993 formulation captured the intuition that when inflation is above target or output exceeds potential, central banks should raise interest rates by more than one-for-one with inflation. This “Taylor principle” ensures that real rates rise when inflation increases, anchoring expectations and preventing inflation from drifting upward.

At this year’s Jackson Hole symposium, Emi Nakamura presented a paper, Beyond the Taylor Rule, co-authored with Venance Riblier and Jón Steinsson. It has attracted wide attention because it asks a timely question: why did central banks react so differently when inflation picked up after covid in 2021–22, and why did they not obey the Taylor principle? The authors’ answer is straightforward, but it forces us to reconsider the role of rules in monetary policy. The positive commentary the paper received prompted me to read it and write this post.

The limits of the Taylor rule

The Federal Reserve’s response to post-Covid inflation was the largest recorded deviation from the Taylor rule. Inflation rose sharply, but the Fed raised rates only gradually. Rather than moving one-for-one with inflation, it chose to “look through” temporary shocks.

Critics saw this as complacency. But by tightening cautiously, the Fed avoided a deep recession and achieved disinflation without a surge in unemployment. The paper argues that this outcome was possible only because the Fed had spent decades building credibility by maintaining low and stable inflation. Expectations therefore stayed anchored, making it easier to return inflation to target.

However, the Taylor rule has never fitted policy rates particularly well. It described US interest rates reasonably closely in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the period Taylor studied in his original work, but it has struggled elsewhere — during the Volcker years, in the post-2008 era at the zero lower bound, and in the recent inflation episode. Attempts to improve the fit by changing coefficients, using alternative measures of inflation or output, or allowing r* to vary risk overfitting. A rule that explains the past too neatly may offer little guidance for the future.

Outside the United States, the Taylor rule is even less accurate. Smaller, more open economies are more exposed to the exchange-rate effects of large interest rate changes. Central banks therefore tread more carefully than the rule would recommend.

When less than one-for-one makes sense

The paper highlights three reasons why central banks may deviate from the Taylor principle, though other concerns also mattered. In particular, raising interest rates by as much as the rule implied would have delivered a massive shock to banks and financial institutions already weakened by the Covid crisis.

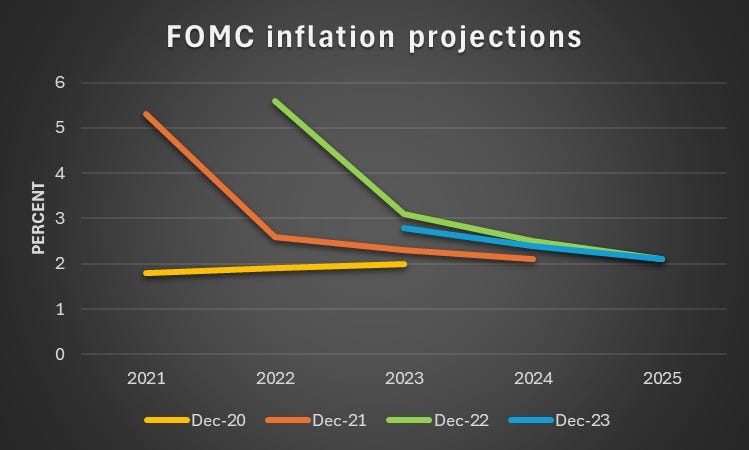

First, transitory shocks. Many central bankers believe monetary policy works with lags of one to three years, so if inflationary shocks are expected to fade before then, sharp rate hikes risk pushing inflation below target later. This was the main reason many central banks hesitated in 2021. The FOMC’s projections illustrate the point: each December from 2020 to 2022, members forecast that inflation would soon fall back, only to be proved wrong. Only in 2023 did their projections align with actual developments.

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Second, correlated shocks. Disturbances often contain both demand and supply elements. A demand boom warrants aggressive tightening. But a contractionary supply shock pushes inflation up while weakening growth. In such cases, strict adherence to the Taylor principle could mean raising rates into a slowdown. Given that Covid had led to a collapse in activity, central banks were understandably hesitant to raise rates dramatically in 2021–22.

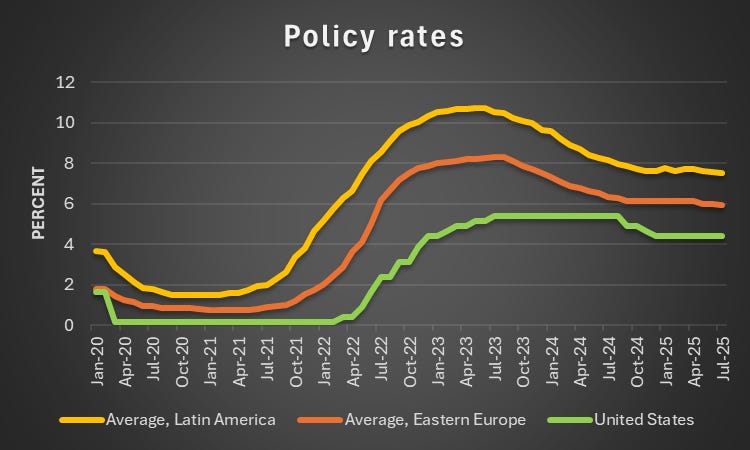

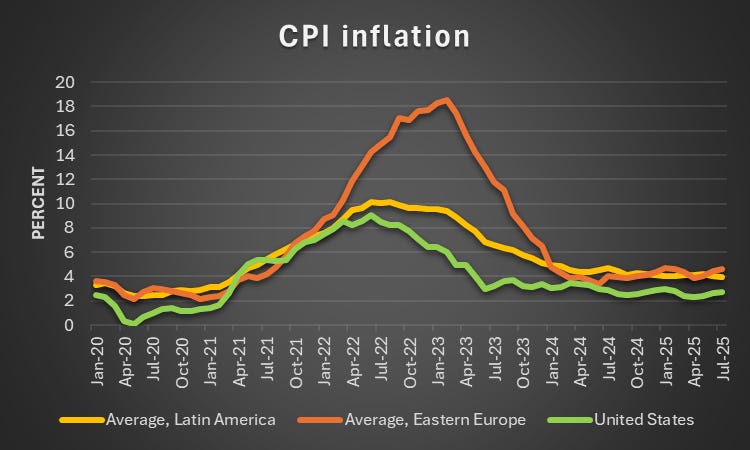

Third, credibility. Strong, trusted central banks can afford to “look through” shocks because markets believe they will deliver on price stability. Weaker central banks cannot. This explains why Latin American and Eastern European central banks raised rates earlier and more aggressively: lacking credibility, they had to act firmly, yet inflation still rose more sharply than in advanced economies.

The charts below illustrate the contrast. Latin American central banks (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) began tightening early and raised policy rates to an average of 10.7%, while Eastern European central banks (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Serbia) lifted theirs to 8.3%. Yet peak inflation was just over 10% in Latin America and nearly 19% in Eastern Europe. By comparison, both interest rates and inflation rose much less in the United States. The lesson is that acting early was not enough without the credibility that anchors expectations.

Source: my calculations on BIS data

Source: my calculations on BIS data

Conclusions

The broader lesson is that credibility defines the scope for discretion. In the 1980s, when memories of high inflation were still raw, there was little room for flexibility. By the 2020s, after decades of stability, the Fed had enough credibility to experiment with a more flexible approach. But credibility is not a permanent asset: repeated deviations could quickly undermine it.

The Taylor rule was not followed in this episode, yet it remains valuable. For central banks with weaker institutions or limited credibility, simple rules send a clear signal of commitment and guard against short-term temptations. And the rule still captures the essential insight that real interest rates must rise when inflation rises, ensuring policy does not drift into pro-cyclical behaviour.

"The broader lesson is that credibility defines the scope for discretion. ... By the 2020s .. the Fed had enough credibility to experiment with a more flexible approach. But credibility is not a permanent asset: repeated deviations could quickly undermine it." This seems to me to be an important conclusion. Applying it to current circumstances, it suggests that the Fed would be taking a risk with its own credibility if it were to be too permissive about a tariff-induced inflation increase, perhaps even a temporary one. The key, both during the post-Covid episode and now, is the anchoring of inflation expectations.

Thank you Stefan for commenting on the paper - now I really want to read it!